News & Press

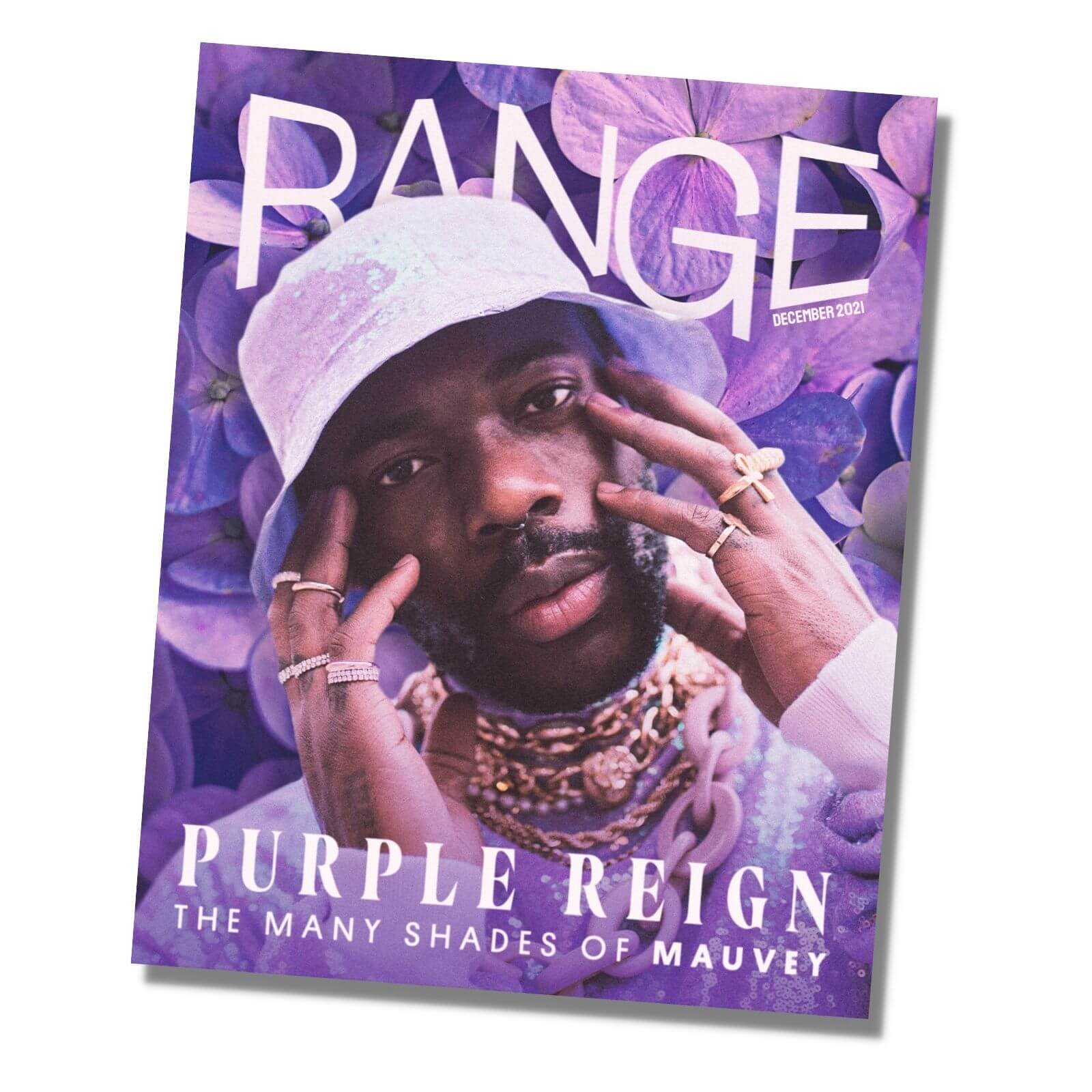

Purple Reign: The Many Shades Of Mauvey | Range

The chameleonic alt-pop artist is leading with love.

Ransford Laryea wades through the crowd at Toronto’s El Mocambo like a sage, greeting people and receiving congratulations for his set. The artist, who performs as Mauvey, just walked off stage from their performance for a national music industry showcase. When we speak shortly after, he tells me, “It feels like the city is calling out to me.” For Laryea, Toronto is a city of dreams. “I got off the plane and I was driving to the hotel, and the CN Tower turned like, mauve, which is the colour that I’ve become attached to.”

“Attached” is putting it softly. As we sit in a stairwell of the concert venue, he’s decked out in his trademark distinction of purple. His corded pants and jacket, the shirt underneath, all mauve. Even his hair is dyed the same soft floral shade. A cursory scroll of his Instagram reveals that this is a near-daily commitment. He says the attachment with purple was born out of an early obsession with the colour’s mutable power. “When trying to figure out what I wanted my artist name to be, I didn’t just want a name, I wanted something that was actually me,” says Laryea, with hands folded over his knees (you can guess the colour of his nail polish). “I felt like it’s the hardest colour to define, you know? It’s a bit blue, a bit purple, it’s a bit grey, it’s a bit silver, it’s a bit pink. It’s a bit of so many things.”

Similarly, Mauvey’s music blurs the lines between alt-pop and hip-hop. There’s a bit of drill, elements of soul, and a bit of hyperpop. “It’s a bit Mauvey.” Laryea was born in Accra, Ghana, where he lived until he relocated to Brixton, a suburb of London when he was four years old. The South London heritage is still evident in his accented speaking voice. While in high school, a basketball exchange program brought him to Agassiz, BC, a small community just outside of Vancouver. Mauvey says it feels like he grew up there as well, and he would return for the occasional holiday. The globetrotting continued, with Mauvey playing basketball in Kentucky, and across Europe. But amid his athletic success, tragedy struck.

“I didn’t just want a name, I wanted something that was actually me.”

Mauvey was in Denmark on Skype, congratulating a friend in America who was drafted into the NBA’s development league. “We were just chatting and then he was like, ‘Yo, I’ll be back.’ And he never came back.” His friend was killed in a hit-and-run that night. The tragedy dislodged his entire sense of self. “It was such a crazy, tragic event,” Laryea says. “I looked at my life in a really different way. I was like ‘what do I actually need to do with my life, what is my purpose with the time that I’ve got?’ I love basketball, but it’s not that.”

The loss sent him reeling, and back home to England. He channeled his pent up emotions into a new outlet: writing. “For like a year and a half I just wrote. I didn’t know it was music at this point.” He tumbled through formats: poetry, short stories, and essays. Eventually the poems morphed into spoken word, and then into his early raps, but there was one problem. “I didn’t know how to do music. I was not trained at all,” Laryea recalls. So he attended open mics, learning the contours of his own voice as he went along, and drawing from the storytelling aspects from the folk, country and soul he grew up with. A new sense of self began to emerge.

“Mauvey came out of the confusion because I never settled on ‘I’m going to be a pop artist.’” Despite this, Laryea developed his singing voice, found a way to rap in his own way, and even embarked on a DIY international tour in 2015. “We did like 20 festivals that summer. I sold out my first hometown show of like 700 people.” What was more gratifying — and draining — was the fact that he basically sold every ticket himself. “I researched the venues, who had played there recently, I connected the support acts myself,” says Laryea, rambling off the list of duties that go into a tour, often facets that concertgoers don’t see. “That’s what it was like, I auditioned a new band in every single city. In-country transport, flights, everything. It was in 2015, for nine months, but that’s where I got the confidence to perform live.”

The tour earned him the attention of management and labels. When he returned to England he was approached by a manager who promised to take him from his DIY roots to interstellar success. “[He said] ‘You’re going to be so big, blah, blah, blah,’ and it’s the first time I was hearing anything, so I really believed it. I was like, ‘oh my gosh, he’s got the contacts to help me.’” The manager asked Laryea for a handful of songs that would showcase his talent to the label. “I like to over-deliver, so I wrote 50 songs.” Laryea also rented a theatre and filled it with friends and family, even making his own visuals to accompany his songs. “And then it was almost like I did too much,” he says. The record exec ultimately realized that Mauvey’s talent outsized his own capabilities, and backed away from promoting him. “He had to be honest because I had put so much in and he just basically broke my heart.”

The let-down demoralized Laryea, and he hung up his music dreams — at least for the time being. What followed was another self-imposed exile, and he turned to the same outlet which comforted the first time. In the spring of 2017, he began going to his local library to write. He would spend 10 hours a day writing thousands of words, chipping away at nothing in particular. Days became weeks, and at the end of four months he had finished a series of psychological thriller novels. “I was like ‘oh my gosh, this is what you are capable of doing.’ Literally, I put the final full stop on the last book and I was like, ‘you’re doing music, you’re not made to just quit and do something regular or cry about the fact that someone’s hurt you, because you can do something, you can alleviate people, you can help people realize that they’re meant for more.’”

“I had put so much in and he just basically broke my heart.”

The music Laryea creates now exists almost in response to that feeling. The performance, and tagline he professes, “distributing love,” becomes more of a discipline or way of being in everyday life. Videos of Laryea delivering flowers to friends and fans became promo for the album. “I don’t actually care about any doubter, or anyone that thinks that it’s inauthentic or whatever, like distributing love is worth more than anyone’s opinion about why someone’s doing something.”

“Irrational,” a single from The Florist, emphasizes that point. In the song, Mauvey doubles down on independence and rejects doubters, shouting on the emphatic chorus, “You know me, I’m never sorry.” The video is a slice of a short film accompanying the album, which of course was directed by Mauvey. He takes on acting duties as well, appearing as several characters, including the Pagliacci-esque sad clown, Mauveylocks. “All of the characters across The Florist short film series are me in some way,” says Laryea. “I think the clown character versus Mauvey, it’s like a pizza. It’s a slice of Mauvey.”

As he describes the video series, and his intention for a limitless stream of future projects — everything from stage designing, to feature films, and revisiting that novel series — his eyes shine with anticipation, as if the future is unfolding just at the end of his vision. For Laryea, the art he makes always returns to fostering love and connection in any way he can. “I want the biggest platform that exists, so from that platform I can say, ‘you’re important,’ so from that platform I can say, ‘you’re worth everything.’”